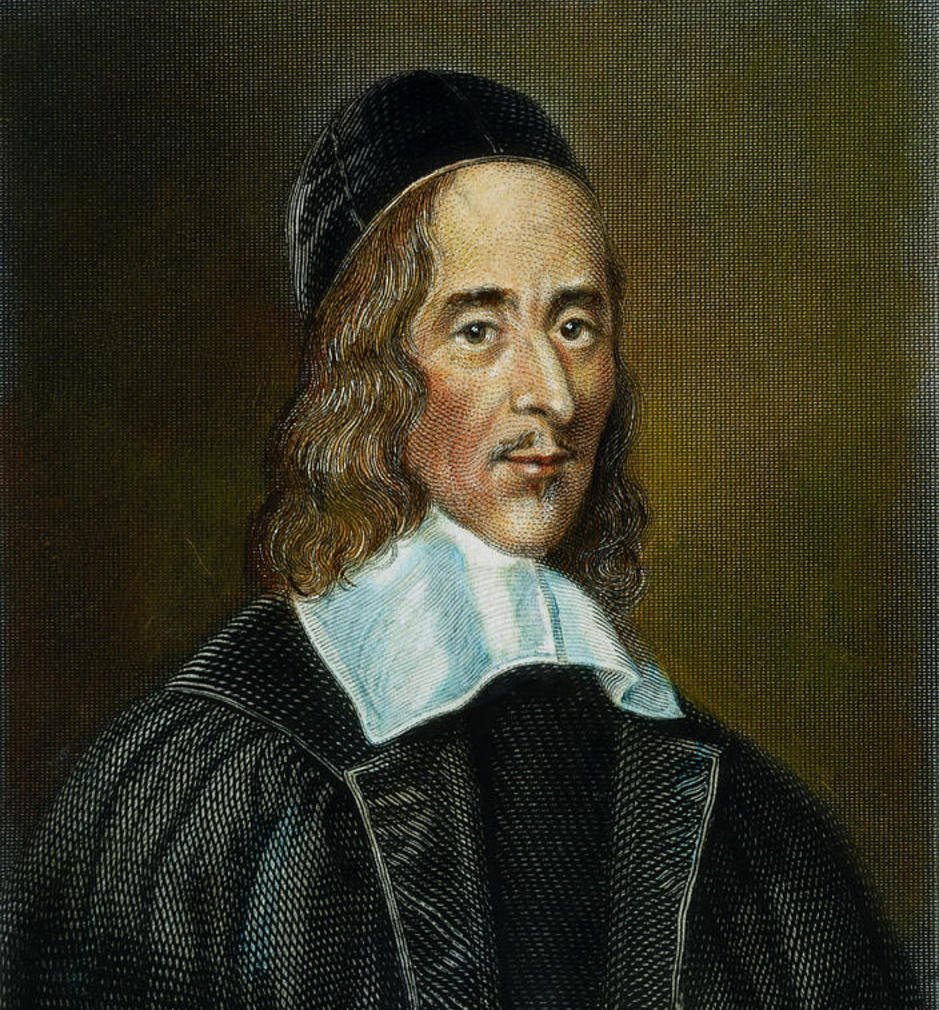

Before the advent of the secular age, Christianity was often a central theme and topic for many European and English poets and writers. The Christian Church was a main part of their everyday lives—participation was expected, even demanded by the governments in power, but personal piety often pushed poets into a deeper, more introspective analysis of who and what God was to them. This is no more evident than in the poems of Richard Crashaw and George Herbert. A close examination of the main ideas, language, imagery, meter, and form in both Crashaw’s “On the Wounds of Our Crucified Lord” and Herbert’s “Easter Wings” aptly demonstrates this assertion.

Regarding the main idea in Crashaw’s poem, “On the Wounds of Our Crucified Lord” (Greenblatt 1644-1645), the speaker attempts to explain his devotion for Jesus Christ and his bodily sacrifice for the sins of the poet and the world. Moreover, this is not merely an intellectual appreciation for Jesus; as he views this figure or effigy of Christ, Crashaw recognizes the multitude of people who physically demonstrate their gratitude for Jesus’ death in how they react to and with this statue probably located within a church. In the end, the poet has connected the characteristics of the statue with the responses to the people, and proved it reasonable and sincere.

The language Crashaw uses is dramatic and powerful, and is utilized to draw attention to the importance of the sacrifice of Jesus. He begins the first half of the poem with O’s and Lo’s—almost an initial yell to get the reader’s attention or perhaps to indicate his immediate awareness and perception elicited from the statue of Christ—“Lo! a mouth...Lo! a bloodshot eye!” (lines 5/7). Additionally, he uses terms associated with an execution or death of a loved one such as bleeding or weeping or crying to connect the reader with the seriousness of the event.

In the second half of the poem, Crashaw switches to a more explanative mode, and uses financial imagery to make his point about the value of Jesus’ death for humanity. Christ repaid the charges of sin for all, and those who understand this show their thankfulness, actively—“Now thou shalt have all repaid, Whatsoe’er thy charges were” (lines 11-12). Their kisses and tears are converted/transferred through Jesus to God. This action of Christ is priceless because he (being God) paid for the crimes of humanity, and gives us the reasons/motivation, too, to kiss his feet in loving devotion.

The meter seems to be iambic tetrameter, which allows for certain words to be emphasized in four measures per stanza. The overall effect in this poem is to create a sort of heartbeat—“Each bleed-ing part some-one sup-plies” (line 4); one could almost hear the poet slowing down with dramatic license near the end of the poem, much like Christ’s heart slowing down before his sacrificial death for humanity. Moreover, many of the words emphasized vocally have poignant meaning to Crashaw’s argument for devotion/appreciation to Christ—“in ruby-tears…in pearls” (lines 19/20).

Crashaw’s poem appears to follow an a-b-a-b pattern, which is the common form of a sonnet—“thine!...eyes?...eyne,…supplies” (lines 1/2/3/4). Even though it would be hard to consider this a romantic poem, it definitely is a love poem, albeit divine, and so his use of the sonnet makes even more sense as many authors (like Shakespeare) used the sonnet in poetry such as this. One almost wonders if Crashaw wanted this to be utilized as a hymn with its simple construction and vocalization; it could easily be put to a tune.

Herbert’s poem, “Easter Wings” (Greenblatt 1609), like Crashaw’s poem, focuses on the efforts of the mighty God to rescue sad, fallen humanity. God created humanity and a wonderful environment in which to live; yet, human beings squandered this gift and since then can only find salvation through a submissive relationship with God. Although Herbert’s believes in the power of God, he expresses his concern that he might fall even farther away if God does not allow him to come together with the Divine again.

Herbert uses widely opposite words and terms in this poem, no doubt to show the lacking of humanity and the majesty of God. Speaking of humanity, he then uses the terms, “foolishly” and “Decaying” (lines 2/3) to juxtapose their realities. The first stanza sets the stage for the reality of humanity; the second stanza shows what can be for humanity with God’s help; the third stanza shows what they are on their own; the final stanza shows what can happen if nothing changes. His argument is persuasive.

This poem has a feudalistic feel to it, with God providing the “wealth and store” (line 1), which His people can also enjoy if they can “combine” (line 17) with God again. He begins the poem with the title, “Lord” (line 1), which indicates a military or royal character of God over the Earth’s inhabitants. All humanity need do is join forces with God, rest under his protective wings (and support), and then they will be victorious and fly high again—“O let me rise” (line 7). Alone, they have no hope of success and will cowardly run away when threatened—“Affliction shall advance the flight in me” (line 20).

The form of this poem is unusual; visually, the first and second stanzas together look like wings as do they third and fourth stanzas. The technical term is Carmen Figuration, and is somewhat unusual. In this poem, it is effective, though, for it gives a visual emphasis to Herbert’s ideas in this poem. The first and third stanzas represent humanity, but without the second and fourth stanzas, the poem (and poet) cannot seem to “fly.” This is a clever (and successful) utilization of this poetical form.

Both Herbert and Crashaw were poetical masters who wove their words into a fine tapestry that was beautiful to view and consider. Yet, their poems, “On the Wounds of Our Crucified Lord” (Greenblatt 1644-1645) and “Easter Wings” (Greenblatt 1609), are not just pretty word pictures—they are poignant examinations of the heart of humanity reaching out to God for help and connection, and both authors pursue this goal, differently. With his utilization of simple poetic meter alongside of powerful terminology, Herbert takes a more aural, almost musical approach to expressing his poem on God than does Crashaw, who takes a visual approach through his use of the Carmen Figuration in his poetical construction. These approaches help ensure the connection of their readers to the poems and their significant messages.

Regardless of their method of delivery, these two poets wear their hearts on their sleeves, and appeal to God’s mercy and grace with each stanza and verse. Every poem may include a main idea, relevant language, imagery, meter, and form, etc., but not every poem is masterfully and successfully brought together. Fortunately for the literary world, Herbert and Crashaw have done just that in these two very personal poems on God and humanity, which is evident to both the eye and to the ear of the reader.

Works Cited

Greenblatt, Stephen, ed., et al. “Easter Wings.” In The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 8th ed. Vol 1. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006.

________. “On the Wounds of Our Crucified Lord.” In The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 8th ed. Vol 1. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006.